Java 8 introduces Stream API, this api comes with classes, interfaces, and enums for processing collection of object (which called Stream). Stream offers basic functional programming capabilities to java: immutability, lazy evaluation, chaining operation, and many more. While the inclusion is pretty good, there are some things that not perfectly ideal. In this post, we’ll go through some of them.

Disclaimer, this is not an exhaustive list and quite likely very subjective. As the title suggest, it’s my rant from working with java stream lately. It also does not rule out the possibility that my rant is due to “skill issue” on my part. That being said, enjoy my rants.

Reduce (or fold) is a higher-order function that recursively process a list to build a return value. For example, we can use reduce to get the sum from a list (or stream) of integer.

int sum = Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

.stream()

.reduce(0, (acc, item) -> acc + item);

// sum == 15

Pretty neat right? We can replace old boring for-loop with more expressive functional style Stream API.

Let’s make it more complicated.

Imagine you want to convert the list of integer into a combined number word string (e.g. [1, 2, 3] -> onetwothree).

String numWords = Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

.stream()

// toNumWords will convert integer to its numwords

.reduce("", (acc, item) -> acc + toNumWords(item));

Simple, just modify our last snippet and we’re done.

Except, it’s not.

If we try to compile the snippet we will be getting compiler error: (argument mismatch; String cannot be converted to Integer).

That’s weird, we have set the initial identity value as an empty string and the accumulator also return string. So, why does the compiler complain about the type?

Even weirder, if we use the 3-parameters, reduce function with combiner as the third parameters it will works as expected.

String numWords = Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

.stream()

.reduce("",

(acc, item) -> acc + toNumWords(item),

(acc1, acc2) -> acc1 + acc2);

// numWords == "onetwothreefourfive"

To understand this, we need to know that in java there are two kinds of streams: sequential and parallel.

As the name suggest, it defined how the stream processed.

For sequential stream, the stream is processed by a single process.

On the other hand, parallel stream will be processed by multiple workers.

To create a parallel stream, we can simply change our stream() method to parallelStream().

final int sum = Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

.parallelStream()

.reduce(0, (acc, item) -> acc + item);

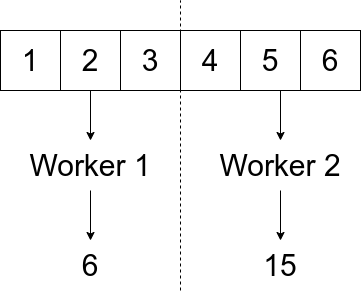

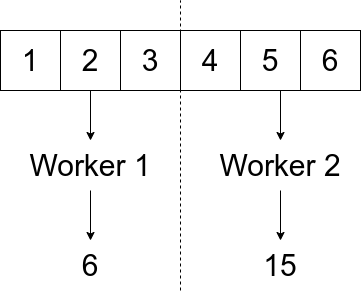

For simplicity, let’s assume that the above snippet will be processed by two thread workers. Worker #1 handle the first part (1, 2, 3) and worker #2 handle the last part (4, 5, 6). Then, we will have two intermediate results: 6 and 15.

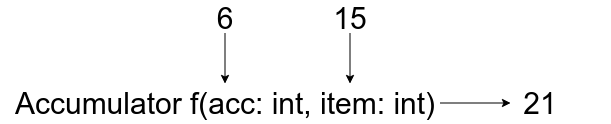

How do we get the final result though? Simple, the reduce api will apply the accumulator function to those results. Because both accumulator result and Stream item type are the same type, applying the function is trivial.

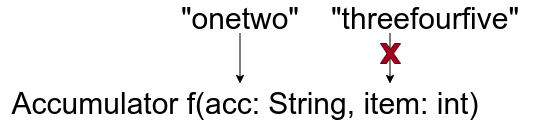

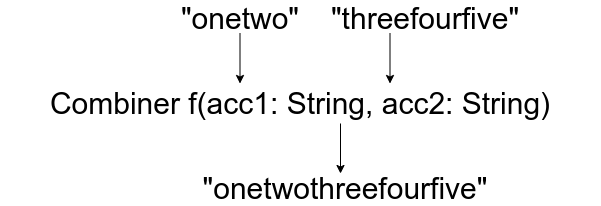

Back to our last failure attempt, because the accumulator function return string while its parameters are string and int we can’t simply use the accumulator function.

Hence, we need the second function, the combiner.

But wait, we weren’t using parallel stream. Hence, the stream should be processed sequentially and combiner isn’t needed. Surely, it doesn’t matter whether we supply the combiner function right? Well, as a matter of fact, it does matter.

You see, the design principle for the stream api is that function implementations shouldn’t be differ between sequential and parallel streams. Quoting an answer on stackoverflow:

A particular API shouldn’t prevent a stream from running correctly either sequentially or in parallel. If your lambdas have the right properties (associative, non-interfering, etc.) a stream run sequentially or in parallel should give the same results.

Hence, we need to provide a combiner function even for sequential stream. We can argue that if the api were designed differently, the reduce function will be much simpler. But, this is design choice and there’s no such thing as the perfect design.

The advantage of this approach is that, we can “simply” change the stream into parallel stream suppose we need it. Although, there are pitfalls and different ways for handling parallel stream compared to the sequential one. Thus, makes it not quite simple to just plug parallel stream in place of sequential stream. Which kinda defeat the whole purpose.

While working with stream (or java in general).

We can’t expect the code to always working smoothly, even more when we are working with user input.

Hence, we have CheckedException to help tackle this in compile time.

Checked Exception will force the programmer to either handle the exception or explicitly declare that a function can throw the exception.

Suppose we have list of json string that we want to deserialize to our POJO using jackson.

Stream<Person> people = Arrays.asList("{\"name\": \"x\"}", "{\"name\": \"y\"}")

.stream()

.map(item -> objectMapper.readValue(item, Person.class));

Because jackson object mapper throw checked exception, JsonProcessingException.

We can declare that our function will also throw that exception.

Stream<Person> parseList() throws JsonProcessingException {

...

But well things aren’t always that simple.

error: incompatible thrown types JsonProcessingException in method reference

.map(item -> objectMapper.readValue(item, Person.class));

^

1 error

It’s due to that how the functional interfaces defined currently prevented exception for being forwarded. (It’s basically oracle fault, but let’s not getting sidetracked here). To handle this, we can wrap our function so it’ll throw unchecked exception instead.

...

.map(item -> {

try {

return objectMapper.readValue(item, Person.class);

} catch (JsonProcessingException e) {

throw new RuntimeException();

}

});

Except that’s ugly and defeat the purpose of the checked exception. Fortunately, good people on the internet has created a hack to workaround this.

public final class LambdaExceptionUtil {

...

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Consumer_WithExceptions<T, E extends Exception> {

void accept(T t) throws E;

}

/**

* .map(rethrowFunction(name -> Class.forName(name))) or .map(rethrowFunction(Class::forName))

*/

public static <T, R, E extends Exception> Function<T, R> rethrowFunction(Function_WithExceptions<T, R, E> function) throws E {

return t -> {

try {

return function.apply(t);

} catch (Exception exception) {

throwActualException(exception);

return null;

}

};

}

...

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

private static <E extends Exception> void throwActualException(Exception exception) throws E {

throw (E) exception;

}

}

Then we can simply use it in our map function.

...

map(LambdaExceptionUtil

.rethrowFunction(item -> objectMapper.readValue(item, Person.class)))

Although, this approach can’t be used for function that throw multiple exceptions.

On that case, the compiler will instead throw the common supertype (e.g. Exception).

For a language that heavily utilize Exception handler, it’s kinda baffling that somehow oracle “forgot” to implement it while making the Stream API. Now that it comes to this, I doubt that this will ever get fixed. Considering fixing this might likely break userland code.

Both issues are quite common to encounter while working with Stream. In fact, both issues has their own discussions on stackoverflow (reduce & checked exception). And this post is my poor attempt on explaining them based on my understanding.

It’s possible that all that problems are insignificant, and it’s due to my lack of understanding of the language that makes it seem irritating. Regardless, there’s one thing that I can’t believe though. Even after all this time, oracle still manages to make my life harder.

← home